Compiz

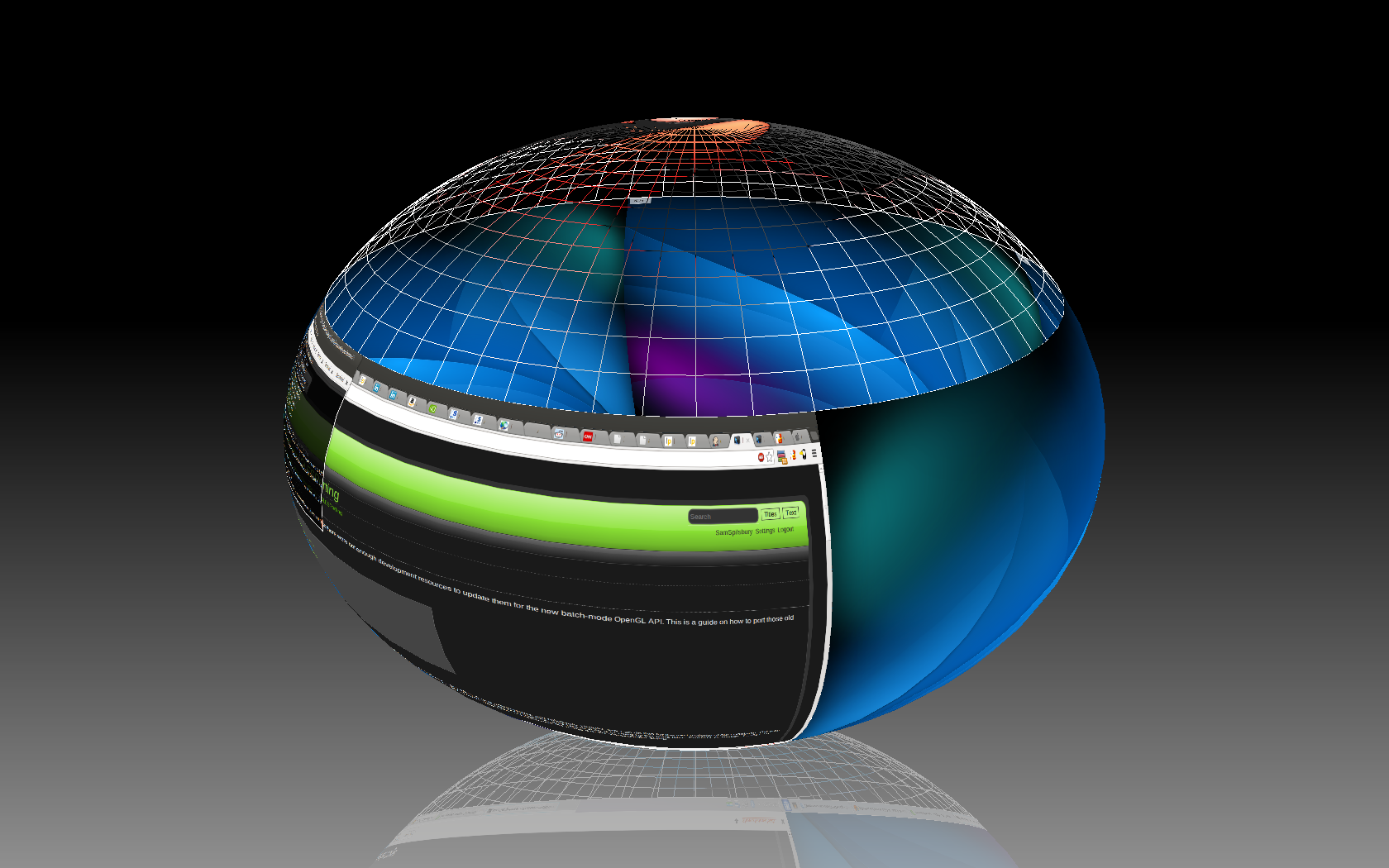

The Compiz project was started in 2006 by David Reveman at Novell. It began as a proof of concept combined window and compositing manager for X11 to showcase the possibilities of rendering the Linux desktop with OpenGL.

Alongside Compiz, Reveman created the (now defunct) XGL implementation of the X.org X Server. That server stored all images making up the windows that you see on your desktop in OpenGL textures. A new extension for OpenGL was created called GLX_EXT_texture_from_pixmap which allowed third party OpenGL clients to obtain the texture handles for windows on the desktop and render them into an OpenGL scene.

Some of the initial demonstrations involved putting virtual desktops on to a cube, or enabling “wobbly” windows using a spring model.

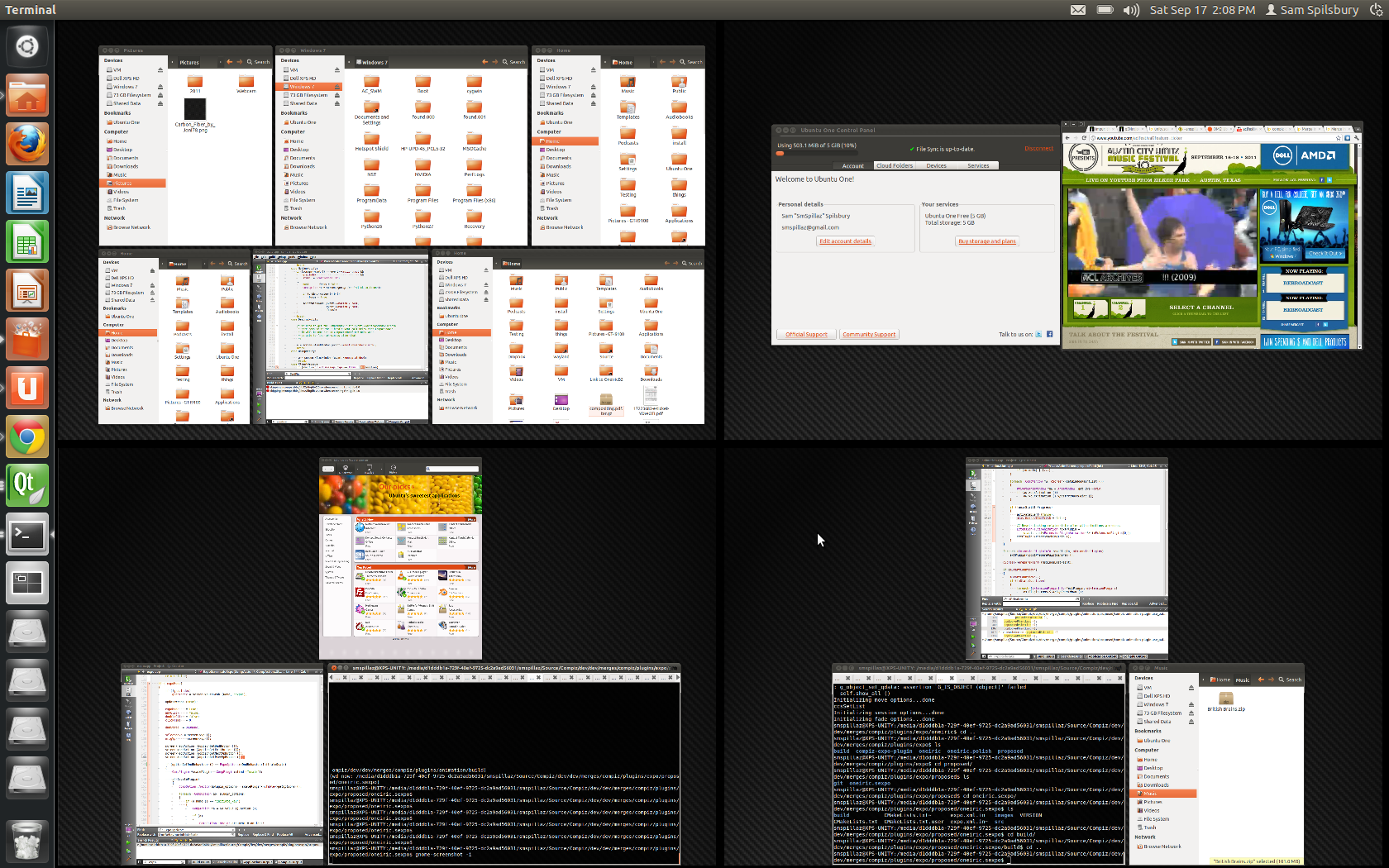

The project exploded with popularity and soon a number of community forks were born and eventually merged back into the mainline project. Development eventually settled on there being a few key developers including myself.

In 2009, among concerns that the codebase was becoming increasingly difficult to work with, an ambitious project began to re-write Compiz in C++ instead of C make some key architectural changes. I assisted with the implementation of this plan and eventually led the development.

By 2010 roughly all 70 plugins had been ported to use the new C++ API and debugged so as to work on the new architecture.

In late 2010, a decision was made at Canonical to use Compiz as the core window manager and rendering platform for the Unity Desktop. Compiz remains the bedrock on which Unity 7, the default Unity Desktop as of 2016, runs today.

Stability

My key priority with Compiz was to maintain the desktop experience that its users had come to love and improve on its overall stability.

Stability had to be approached from two angles.

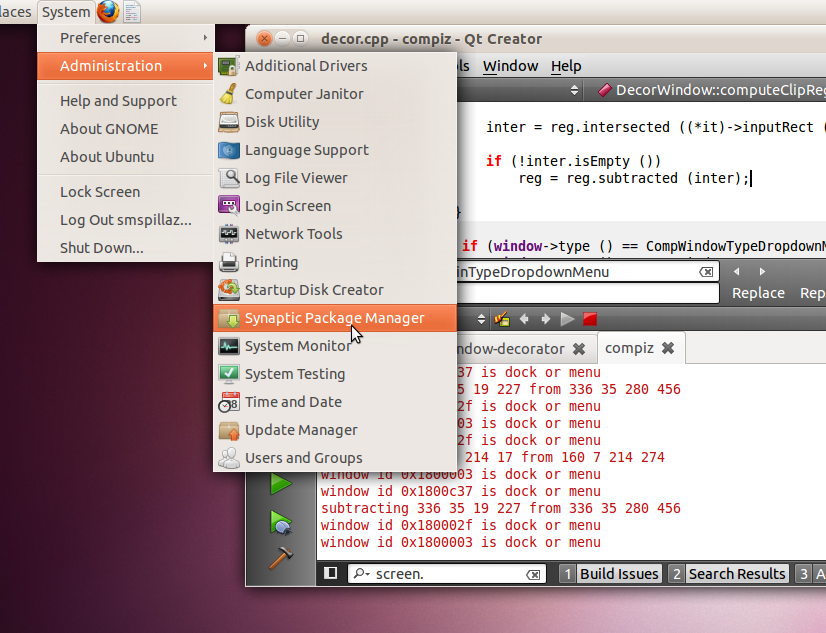

The first angle was about getting to understand the domain the project operated in. X11 Window Managers and Compositing Managers use the same protocol to communicate with the X Server as individual client applications use to create their windows. The only difference is that the window manager has special privileges to override how windows are to be placed, sized and stacked.

This in turn meant understanding the various ways in which client applications might attempt to use the X11 protocol to achieve their objectives and also understanding how to work with the snapshot of reality a Window Manager gets as “another client” of the X Server. In particular, the window manager is only notified of certain events after they occurr and is only able to restrict client windows from engaging in certain operations. In particular, there are other windows which are free from control by the window manager and risk associated with that needed to be mitigated appropriately.

The second angle was about ensuring that given the project’s overall code complexity as a “legacy” codebase, there were no regressions every time a bug was fixed. I worked other engineers to devise an incremental, but evetually comprehensive testing strategy. There are now more than 1500 tests, including around 100 acceptance tests which are run on every build. These tests ensure that a range of “odd” situations created by third party applications are handled in a way that does not cause undefined behaviour or behaviour that is outside of user expectations.

Both of these approaches led to an overall reduction in defects and increased compatibility with clients. They were both instrumental in fixing longstanding problems where the window stacking order would become undefined and result in a poor experience for the user.

OpenGL|ES Support

Another key area of development was to migrate the “legacy” OpenGL renderer to a model that would support both OpenGL|ES and OpenGL 2.0+.

This project was done in collaboration with developers from Collabora and Linaro. The fixed funtion renderer was replaced with a renderer that used vertex buffer object and GLSL shaders. All the plugins making assumptions on the old renderer needed to be updated to support the new renderer.

Some key areas of innovation were to introduce initialisation code that could support both EGL and GLX, introduce a shader cache and shader builder so that plugins could “chain” shaders, introduce rendering to framebuffer objects such that plugins could add postprocessing effects and more.

The project was completed and distributed to users in early 2012. By that point, Compiz could be run both on the free software OpenGL|ES drivers and on ARM Mali devices.

Performance

Compiz was selected for being a performant compositing manager and it was important that this performance was maintained.

Performance optimistion primarily came from hand-optimising the renderer using tools such as apitrace and callgrind.

There were numerous other performance wins derived from rendering features added to the core.

One such performance outcome was achieved by compressing the amount of traffic sent to and from the X Server when Compiz was manipulating a window. For certain graphics drivers that used a lot of internal locking, this substantially improved rendring performance whilst other OpenGL applications were rendering.

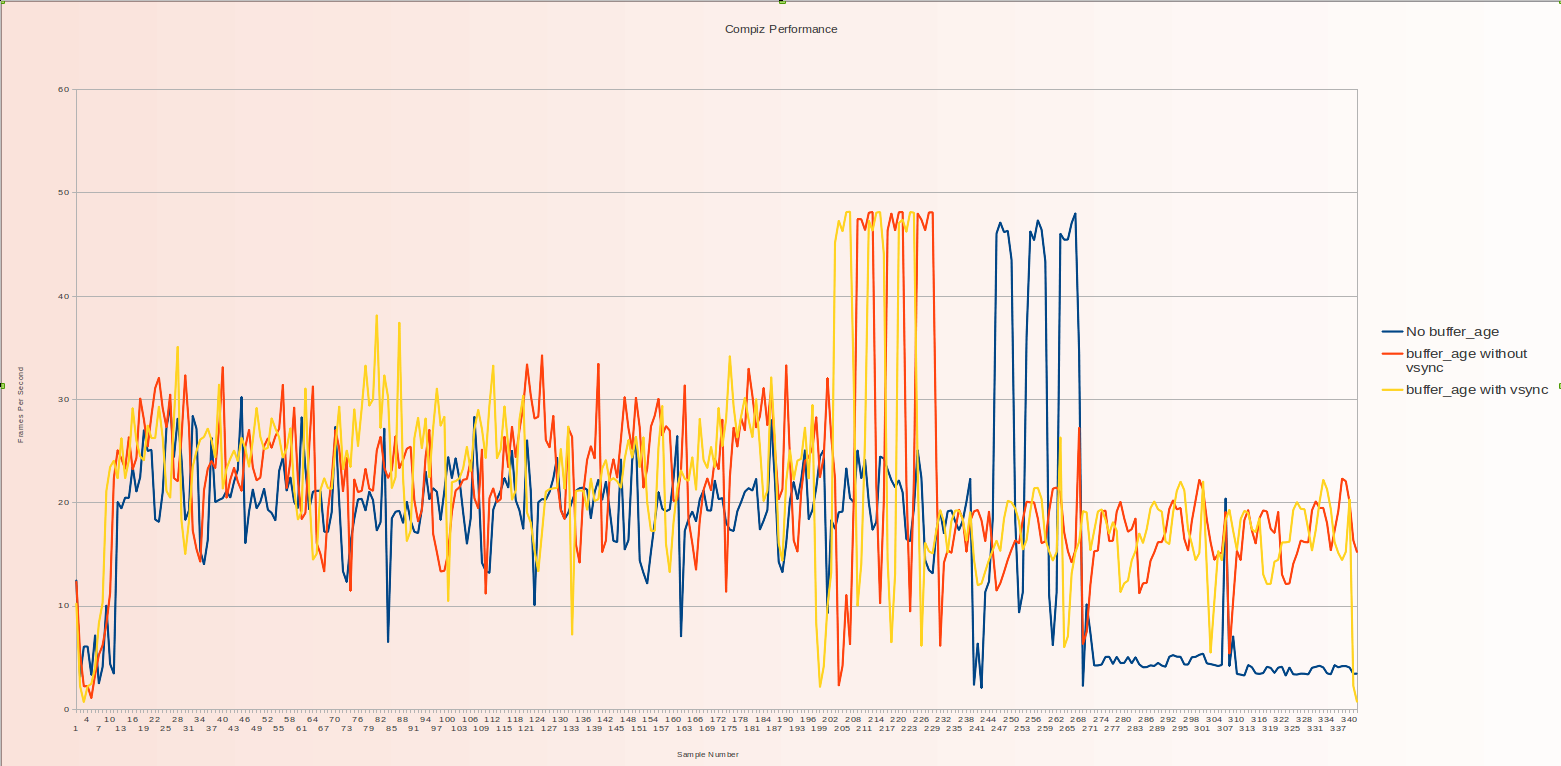

Another performance outcome was achieved by implementing the

GLX_EXT_buffer_age extension designed in 2013. This extension allows for

applications to reason about the backbuffer when SwapBuffers was called

in the driver. Previously, the contents were undefined. With the extension,

the number of swaps since the backbuffer was written to became available. An

implementation in compiz involved tracking what regions of the screen had been

updated on every buffer swap and storing this within queue. The other plugins,

as well as the Unity Desktop, needed to be fixed to ensure that these regions

were being updated correctly.