Bringing back the old animations

One of the other casualties when we switched to using Modern OpenGL in Compiz was the loss of the older animation plugins, such as animationaddon, simple-animations, animationjc and animationsplus.

I took some time last weekend to make the necessary changes to bring them back to life and get them merged back into mainline.

One of the more interesting parts of all this was the polygon-based animations. You might remember this as the “glass shatter” or “explode” animations. Unlike most of the other code in Compiz plugins that did transformations on windows, the “polygon animation” mode actually completely took over window drawing. This meant that there was a lot more work to do in terms of getting them to work again.

glDrawElements

Compiz has had (for a few years now) a class called GLVertexBuffer which encapsulates the entire process of setting up geometry and drawing it. If you want to draw something, the process is usually one of getting a handle for something called the “streaming buffer”, resetting its state, adding whatever vertices, texture co-ordinates, attribute and uniform values you needed then calling its render method.

Under the hood, that would populate vertex buffer objects with all the data just before rendering and then call glDrawArrays to render it on screen using the defined vertex and pixel processing pipeline.

glDrawArrays can be cumbersome to work with though, especially with primitive types where you might end up having a lot of repeated vertex data. You have to repeat the components of each vertex for every single triangle that you want to specify.

glDrawElements on the other hand allows you to set up an array of vertices once, adding that array to the vertex buffer, then specifying a little bit later the order in which those vertices will be drawn. That means that if you were drawing some object in which triangles always had a point of (0, 0, 0), then you could just refer to that vertex as “1”, so long as it was the second vertex in the vertex buffer. This is very handy when you have complex 3D geometry.

Quite understandably, animationaddon’s polygon animation mode didn’t use glDrawArrays but glDrawElements.

In order to support both OpenGL and GLES it was necessary add some sort of support for this in GLVertexBuffer, since the old code was using client side vertex and attribute arrays. The quickest way to do this was to just add some overloads to GLVertexBuffer’s render method, so now as a user you can specify an array of indices to render. Its a little more OpenGL traffic, but it makes things a lot easier as a user.

Re-tessellation

All the geometry for those 3D animations was rendered using the GL_POLYGON primitive type. Polygons are essentially untesselated concave shapes. GLES only supports triangles, triangle fans and triangle strips which threw a spanner in the words.

The polygon animation mode supported splitting windows into rectangles, hexagons and glass shards.

At first I was wondering how to convert between the two geometries, but it turns out that for concave shapes there’s an easy way to split it up into triangles. Just take a reference point, then make a line from that reference point to each of its neighbours, bar its neighbours.

That can be represented with this simple function:

<span class="pyg-k">namespace</span>

<span class="pyg-p">{</span>

<span class="pyg-k">enum</span> <span class="pyg-k">class</span> <span class="pyg-nc">Winding</span> <span class="pyg-o">:</span> <span class="pyg-kt">int</span>

<span class="pyg-p">{</span>

<span class="pyg-n">Clockwise</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-mi">0</span><span class="pyg-p">,</span>

<span class="pyg-n">Counterclockwise</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-mi">1</span>

<span class="pyg-p">};</span>

<span class="pyg-cm">/* This function assumes that indices is large enough to</span>

<span class="pyg-cm"> * hold a polygon of nSides sides */</span>

<span class="pyg-kt">unsigned</span> <span class="pyg-kt">int</span> <span class="pyg-nf">determineIndicesForPolygon</span> <span class="pyg-p">(</span><span class="pyg-n">GLushort</span> <span class="pyg-o">*</span><span class="pyg-n">indices</span><span class="pyg-p">,</span>

<span class="pyg-n">GLushort</span> <span class="pyg-n">nSides</span><span class="pyg-p">,</span>

<span class="pyg-n">Winding</span> <span class="pyg-n">direction</span><span class="pyg-p">)</span>

<span class="pyg-p">{</span>

<span class="pyg-kt">unsigned</span> <span class="pyg-kt">int</span> <span class="pyg-n">index</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-mi">0</span><span class="pyg-p">;</span>

<span class="pyg-kt">bool</span> <span class="pyg-n">front</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-n">direction</span> <span class="pyg-o">==</span> <span class="pyg-n">Winding</span><span class="pyg-o">::</span><span class="pyg-n">Counterclockwise</span><span class="pyg-p">;</span>

<span class="pyg-k">for</span> <span class="pyg-p">(</span><span class="pyg-n">GLushort</span> <span class="pyg-n">i</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-mi">2</span><span class="pyg-p">;</span> <span class="pyg-n">i</span> <span class="pyg-o"><</span> <span class="pyg-n">nSides</span><span class="pyg-p">;</span> <span class="pyg-o">++</span><span class="pyg-n">i</span><span class="pyg-p">)</span>

<span class="pyg-p">{</span>

<span class="pyg-n">indices</span><span class="pyg-p">[</span><span class="pyg-n">index</span><span class="pyg-p">]</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-mi">0</span><span class="pyg-p">;</span>

<span class="pyg-n">indices</span><span class="pyg-p">[</span><span class="pyg-n">index</span> <span class="pyg-o">+</span> <span class="pyg-mi">1</span><span class="pyg-p">]</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-p">(</span><span class="pyg-n">front</span> <span class="pyg-o">?</span> <span class="pyg-p">(</span><span class="pyg-n">i</span> <span class="pyg-o">-</span> <span class="pyg-mi">1</span><span class="pyg-p">)</span> <span class="pyg-o">:</span> <span class="pyg-n">i</span><span class="pyg-p">);</span>

<span class="pyg-n">indices</span><span class="pyg-p">[</span><span class="pyg-n">index</span> <span class="pyg-o">+</span> <span class="pyg-mi">2</span><span class="pyg-p">]</span> <span class="pyg-o">=</span> <span class="pyg-p">(</span><span class="pyg-n">front</span> <span class="pyg-o">?</span> <span class="pyg-n">i</span> <span class="pyg-o">:</span> <span class="pyg-p">(</span><span class="pyg-n">i</span> <span class="pyg-o">-</span> <span class="pyg-mi">1</span><span class="pyg-p">));</span>

<span class="pyg-n">index</span> <span class="pyg-o">+=</span> <span class="pyg-mi">3</span><span class="pyg-p">;</span>

<span class="pyg-p">}</span>

<span class="pyg-k">return</span> <span class="pyg-n">index</span><span class="pyg-p">;</span>

<span class="pyg-p">}</span>

<span class="pyg-p">}</span>

Depth Buffer

We never really used the depth (or stencil buffers) particularly extensively in Compiz, even though the depth buffer is a common feature in most OpenGL applications.

The depth buffer is a straightforward solution to a hard problem - given a bunch of geometry, how do you draw it so that geometry which is closer to the camera is drawn on top of geometry that is further away?

For simple geometry, the answer is usually just to sort it by Z order and draw it back to front. For the vast majority of cases, compiz does just that. But this solution tends to break down once you have a lot of intersecting geometry. And those animations have a lot of intersecting geometry.

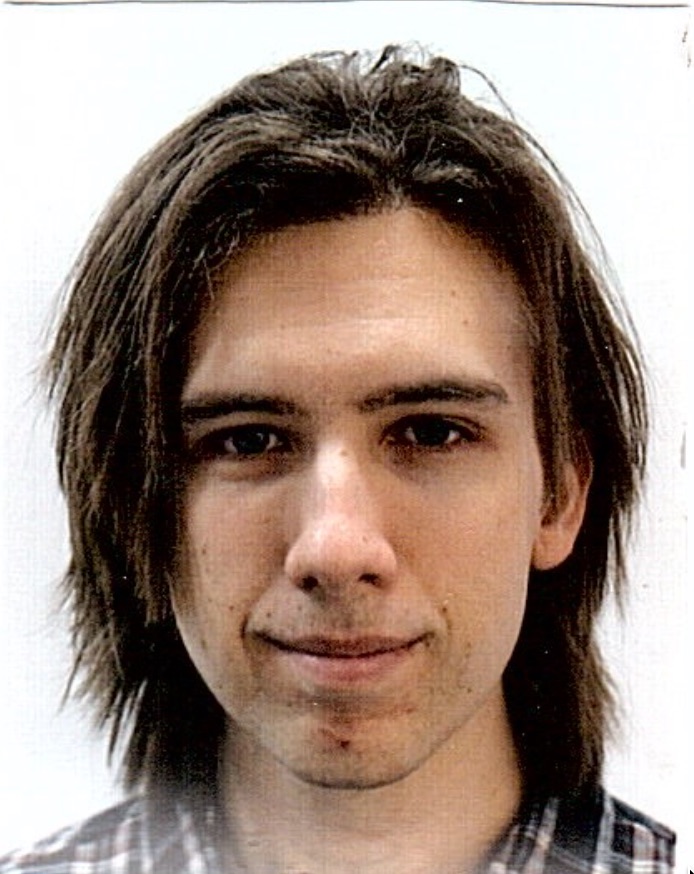

Note in this image how the white borders around each piece are drawn on top of everything else?

The better alternative is to use the depth buffer. It isn’t perfect and doesn’t allow for transparency as between objects whilst the depth buffer is enabled, but it does handle the intersecting geometry case very well.

The way it works is to create an entirely separate framebuffer where each “pixel” is a single 24 bit floating point number. Compiz uses an implementation where the other 8 bits are masked out and used for the stencil buffer. Every time OpenGL is about to write a pixel to the framebuffer, it keeps track of how far away that pixel is in the scene. It does that during something called the “rasterisation stage”. This is where a determination is made as to where to draw pixels. That’s done by interpolating between each vertex to reach a position and its relatively trivial to keep track of depth too by similar methods. Then, OpenGL compares the depth to the existing value at that position in the depth buffer. The usual depth test is GL_LESS - so the value in the depth buffer is updated and the framebuffer write is allowed.

The result is that parts of geometry which were already occluded are simply not drawn, where as geometry which occludes other previously-drawn geometry overwrites that geometry.

I this image, you’ll notice that each piece correctly overlaps each other piece, even if they are intersecting.

Trying it out

The newly returned plugins should be back in the next Compiz release to hit Yakkety. They won’t be installed or enabled by default, but you can install the compiz-plugins package and compizconfig-settings-manager to get access to them.

If you’re ever curious about how some of those effects work, taking the time to re-write them to work with the Modern OpenGL API is a great way to learn. In some cases it can take a lot of head-scratching and debugging, but the end result is always very pleasant and rewarding. There’s still a few more to do, like group, stackswitch and bicubic.